Anna McClellan Turns the Light Back On

Catching up with the songwriter about Omaha, working in TV, and her magnificent new album, Electric Bouquet

In the heady days of early 2016, I went to see Frankie Cosmos play at Swedish American Hall in San Francisco. The show featured a full lineup including an opener named Anna McClellan. Anna’s set began with her seated at a piano, angled slightly away from the crowd, peering at us through wire-framed glasses. I felt a bit nervous on her behalf, having seen too many coastal American crowds talk over an opener’s set as if they’re a nuisance to be waited out. Anna’s performance that night was completely disarming and I remember it as clearly as if it were last week: piano and voice combining as seemingly sparse parts into something nearly overwhelming.

In between her plucky songs, we learned more about Anna’s story: she hailed from Omaha, Nebraska and had been invited to join the tour by Greta Kline (the singer and songwriter of Frankie Cosmos). Kline and the band came out to accompany Anna on her final songs and the energy in the room crescendoed with a palpable sense of gratitude. I felt sure of having been introduced to someone’s music that I would likely never forget.

Anna and I spoke on the phone last month, on Halloween - she was reporting from a quiet bar patio in Austin, kölsch in hand, having spent the past few months living in the Texas capitol. Her new album Electric Bouquet was released in October, on the San Francisco-based label Father/Daughter Records, who helped bring Anna’s two previous full-length records into the world. She had met Jessi Frick, the label’s co-founder, in passing and having already recorded an album’s worth of songs and shortly after their meeting, she emailed Frick with the recordings and asked if the label would be interested. “She was down,” Anna remembers, “and that label is one of the best things that’s ever happened to me.” Frick and the label are able to “straddle two worlds” as Anna puts it: operating with savviness in the music industry and with a sense of care in nurturing its roster of artists.

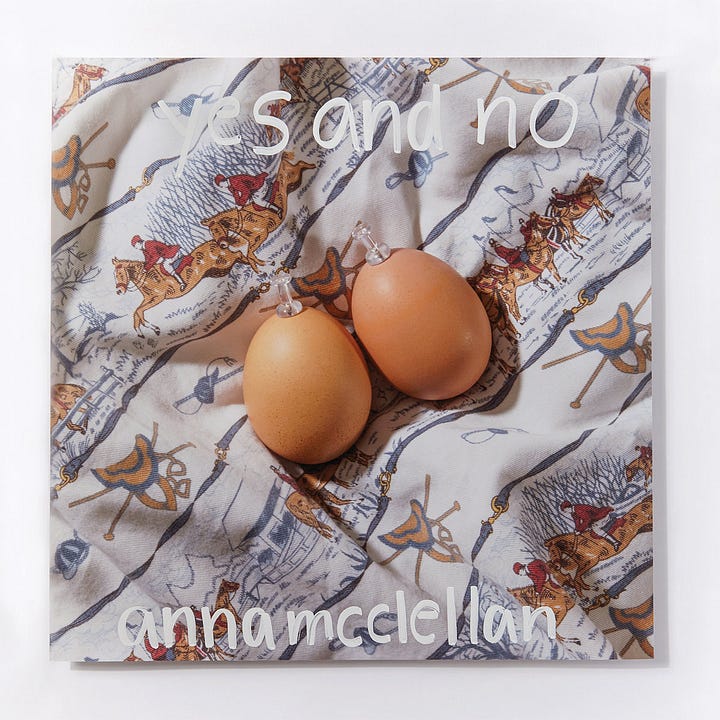

Yes and No, released by F/D in 2018, remains an absolute favorite of mine: a tender and clear-eyed portrait of youthful uneasiness, lifted up and sewn together by Anna’s freewheeling piano and her unmistakable voice. The songs have an aching heart of Americana in them, but there’s no illusory patriotism when it comes to the rottenness of being alive in contemporary America. At the crescendo of “Heart of Hearts” she delivers a searing line, both a critique and a statement of solidarity, “we all feel the weight of a system that is rigged, forced to act in spite.”

The 2020 follow-up I Saw First Light was produced over the span of a couple weeks around the time Anna moved back to her hometown of Omaha, after a couple-year stint in New York City. Buoyed by her artistic community and several collaborators, she crafted a record that is more expansive than its predecessor. Whereas Yes and No exudes a bodily warmth, as if you’re seated next to Anna at the piano, First Light is looser, a bit chillier, world weary. I felt a bit out of step with the record when it came out, but upon revisiting I’ve found it to be authentically of its time. The songwriting rolls together generational disillusionment and rage, a longing for community, and a hunger for justice in a way that feels true to the explosive nature of the year it came out, but not simply as a time capsule. At that time, it was fashionable to make music with a removed posture of “what’s going on?” Anna succeeded in doing the harder thing: making songs about what was going on with her, but allowing them to feel like they could be about any of us.

Nearly a decade after her first full-length release comes Electric Bouquet, which was composed, as Anna says, in a solitary place, “my own little church, where I go to pray.” She is admittedly uncompromising when it comes to creating the songs and giving them their structure, fiercely protective of her own writing. And it’s not entirely glamorous, as she wryly notes, “I spend a lot of time sitting and doing nothing, that’s part of my process. I sit at the piano and pick at my fingers for a while, probably spending more time not playing than actually playing.” She jokes, astutely, “It’s not very satisfying, but that’s what writing is.”

The songs on EB all began in Anna’s music room at her house in Omaha, but not all at the same time. The piano-centric “Jam the Phones” and “Endlessly” were written in 2020, the shape of those songs bearing a resemblance to much of the previous records. In summer of 2022, she traveled to Baltimore and tracked “I’m Lyin” and “Paper Alley” with close friend Ryan McKeever, of the band Workers Comp. Feeling a head of steam, the plan was to finish recording the rest of the album over the course of that summer, but life got in the way as it’s want to do. The following March, Anna booked a week of studio time at Another Recording Company (of Bright Eyes fame) in Omaha, and alongside McKeever and ARC engineer Adam Roberts, finished the record.

Despite her protectiveness of the writing phase, Anna welcomed input when it came to the arranging and recording of her songs, and both McKeever and Roberts were hands-on with their contributions, the former lending his voice to “Co-Stars” which was written during the studio week. This collaborative, made-by-many-hands approach to the recording can be felt deep in the fabric of the songs. My image of Anna remains fixed somewhat on the solitary figure seated at the piano in San Francisco, but I described to her the image conjured when listening to Electric Bouquet, of a living room jam session with friends. Anna anchors the songs with her distinctive voice and sensibility but there’s a looseness in the background, someone new sitting at the drums or picking up the bass while it’s owner gets up to snag a beer from the fridge - not missing a beat and adding some new color or rounded edge to the sound. They’re not seeking attention or showing off, just doing their part in service of the songs.

Anna responded to this metaphor by tying it back to something we had discussed earlier: a true DIY ethos. The acronym gets thrown around a lot in music circles, it can describe a certain low-fidelity sound but it better embodies a way of life: booking your own tour, printing your own t-shirt, sleeping in the van, the van breaking down, etc. Anna provides a thesis on what DIY means to her: something existing only for the sake of itself.

She’s thought through this definition endlessly, having spent the better part of her life in and around various DIY music scenes, primarily in Omaha. After departing a few-year stint in New York City in 2019, amid a state of deep personal uncertainty, she landed back in her hometown and began the process of, as she describes, “fixing myself up.”

I was curious about her relationship with the city given the nature of the album’s standout song, “Omaha” which seems to express a somewhat forlorn feeling in the closing line “wilting til I rot, Is it me or is it Omaha?”

Anna assures me that the relationship is one of “only love”, that her time living there, “allowed me to process a lot of things personally but also in a community way. That’s what the song is about: we’re all here and making cool stuff together but why does it feel fraught? I want to talk about this! What is our scene and what does it mean to us? What do we want it to feel like and how do we make it feel that way?”

These were not idle questions for our phone call. Anna was part of a movement in Omaha in the wake of the pandemic to organize public dialogues for and about the artistic community there. The dialogues were co-facilitated with Mary Lawson, artist and founder of the Omaha Music Coalition. On her collaborator, Anna noted, “Mary had separately been asking these questions about the scene in Omaha, which like most any midwestern music scene through the ages, is dominated by white men. So we began by asking how do we give attention and divert attention to other things that are happening, make the scene more diverse, and how do we actually flow the economy towards the collective?”

Recognizing that these sorts of discussions are so often solutions-oriented, Anna argued for listening over fixing, having seen that “in any activist space it’s always ‘what are we gonna do?’ or ‘how are we gonna fix these problems?’ and I was more into let’s just talk without trying to come to some conclusion. Let’s do that as long as we need to because everyone just wants to be heard.” She likened this need to be heard to being a child who’s upset about something and having a parent swoop in and immediately try to offer a solution, “no mom I just want someone to listen to me!”

Anna and Mary’s methodology in the dialogues may seem counter-productive, but the convenings were predicated on the idea that if more voices are in the room and everyone has a chance to be heard, solutions will naturally rise to the fore. They also sought to counteract the individualism and transience that can often define a city’s music scene. Anna points to an “I’m doing this for me and my art” mindset that is ultimately harmful when trying to navigate a destructive system, and Mary would often return to the question of how their peers would go about building a stronger artistic community for the next generation. Music scenes, especially in smaller cities, have a tendency to die out every few years when enough people leave town or a certain bar or cafe closes its doors.

In the wake of these dialogues, Anna sensed a real shift in Omaha, “something rising up,” a new feeling of “not forcing our intentions to happen, but just by talking and listening to each other stuff started to happen.” At the same time, she had found herself on an unexpected new career trajectory. She had been working at beloved local wine bar La Buvette but admitted, “I was getting drunk too much and I needed a different way to make money.” On a whim, she enrolled in electrician classes at her local community colleges and began her way toward an Associate’s degree. A plan began to form: get the degree, then find somewhere else to live. It could seem like a perplexing choice, to leave a place that you love and where you are a fixture in your community. For Anna, this comfort was outweighed by “a curiosity about my own potential, what I could do if I wasn’t constricted to all these identities: a niece, or a classmate from elementary school or whatever.” It was a dilemma I understood well, having faced it when deciding to move to New York. I suggested that what Anna had seen in Omaha as she was preparing to leave, a renewed energy around the music scene, was actually as good a sign as any that it was time to go. Better to leave without bitterness, and with the knowledge that things are going to continue on without you. “That’s such a beautiful thing about Omaha,” she answered, “it’s a real community, out in the middle of nowhere where no one knows what’s going on there. It exists just for itself, and I feel so lucky just to know what’s going on there.”

During her final summer in Nebraska, while she was completing an internship for a construction company working on the expansion of a meatpacking plant, Anna made up her mind to move to Los Angeles and try getting work in television. A friend of a friend helped her get hired as a lighting technician on 1923, the period western starring Harrison Ford and Helen Mirren that is part of Taylor Sheridan’s Yellowstone-verse. The show is shot between Montana and Texas, hence her being in Austin, and the experience of working on set was, “a fucking trip” as Anna put it. She found herself thrust into an entirely new world and industry, working as a fixtures technician to look after any lighting element that appears on screen, which meant wiring a ton of lamps with period-accurate fabric wire. Being a part of the machine of a big-budget show was overwhelming but there was an undeniable thrill in her voice as she talked about it.

The job finished earlier this year, and Anna isn’t sure what’s coming next for her but she is taken with the idea of making television. On the phone, she reported she had just checked out a stack of books on screenwriting from the Austin Public Library, musing, “as an artist or an entity, I’m a writer. That’s where I live and exist in creating narratives.” When I asked if there’s an Anna McClellan-penned pilot script in the works, she chucked but referred pointedly back to the question of potential, “what can I do? What can any of us do? Just go and do it - fuck it!”

In her alone time in Texas, she’s also in the process of booking a tour for 2025, doing it herself as she always has. “It’s scary,” she admits, “none of this just happens, you have to figure it all out. But, then, I’ve figured it out all the other times. It just takes a bit of blind faith.”

As we finished our call, I asked Anna what was inspiring her at the moment. She pondered, then reported that she was enjoying reading again after so many months away from home working, that it was helping her “come back to myself.” She left me with an anecdote from a few days prior: among the books checked out from the library was a collection of poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay. As a sort of exercise, she sat in her car, parked outside a bar in Austin, and read “Renascence” aloud with the windows down. Paying no mind to the eavesdroppers, she felt the act of reading aloud, of hearing her own voice, “like a cool way of coming back into the world and staying connected to life, staying in touch.”

But, sure, the sky is big, I said;

Miles and miles above my head;

So here upon my back I'll lie

And look my fill into the sky.

And so I looked, and, after all,

The sky was not so very tall.

The sky, I said, must somewhere stop,

And—sure enough!—I see the top!

The sky, I thought, is not so grand;

I 'most could touch it with my hand!

And reaching up my hand to try,

I screamed to feel it touch the sky.

From “Renascence” by Edna St. Vincent Millay