From the past year of going to the movies, one particular costume choice has stuck with me. It’s not the Jonathan Anderson-selected plaid Nike tennis shorts from Challengers. Or the infamous green-and-white-polka-dot smock from A Complete Unknown. Not even Adrien Brody’s deep bench of mid-century knitwear as seen in The Brutalist. It appeared, unexpectedly, in the underseen A24 drama Sing Sing - based on the true story of Rehabilitation Through The Arts (RTA), a program started in the mid-90s at the Sing Sing Correctional Facility in Ossining, New York. The film follows a group of incarcerated men taking part in RTA’s theater workshops as they prepare to stage a production inside the prison. During a rehearsal scene early in the movie, the film’s star Colman Domingo is shown seated among his fellow theater artists wearing a pristine purple hooded sweatshirt over his forest green prison uniform.

It’s a subtle choice that creates such a striking image, and all the more powerful for going unremarked upon. We’ve already seen John “Divine G” Whitfield (a real-life RTA participant portrayed by Domingo) in his state-issued two piece set and we understand the uniformity to be part of the point. Incarcerated people are required by the institution to dress alike as a means of surveillance and control, any item of “civilian” clothing disallowed with only rare exceptions like appearing in court. It’s not explained how Divine G came to possess the sweatshirt (my best guess a Hanes EcoSmart) or if he’s allowed to wear it only while participating in a workshop. It’s just there, on his body, but by no means an accident. Costuming is always a choice.

Domingo’s character is portrayed as the undoubted leader of the theater troupe and a sort of celebrity at Sing Sing. In addition to being a committed legal researcher and advocate while behind bars, Divine G also authored four novels and many of the plays that would go on to be staged in the prison through Rehabilitation Through The Arts. An early scene in the film shows a man sitting beside Domingo in the cafeteria and asking for his autograph - it’s the real Whitfield sheepishly praising his own avatar. The plays he writes have become the bread and butter of RTA in Ossining, but they tend toward drama and complex characters. A new member of the group, Divine Eye, whom Whitfield recruited to join, objects to the seriousness of the subject and sways the group toward a devised comedy. Divine G, sharply aware of what his presence means to the production, relents with only a hint of wounded-ness.

By its placement in the film, the purple hoodie confers unto Divine G a certain nobility. He has forgone his own artistic ego for the good of the group and as a welcoming gesture to Divine Eye, who the film sets up as his foil. Divine G throws himself into the theater exercises: effortlessly flexing his skills in movement, voice, and character. In contrast, Clarence “Divine Eye” Maclin (who plays himself) is stiff and reluctant. But despite his rawness and temperamentality, he climbs gracefully into the production’s central role. It’s an astonishing two-fold feat: the filmic Divine Eye bowls over his colleagues by unlocking vulnerability, while the living Maclin plays this version of himself with a captivating naturalness.

Throughout history, the color purple has been associated with royalty as the dye required to conjure it was expensive and exclusive. In the spartan confines of prison, where even the humblest of possessions hold the highest meaning, a clean cotton sweatshirt carries the weight of a majestic garment. Once again in contrast, Maclin is depicted in two scenes wearing a conspicuously yellow t-shirt under his uniform. Another subtle color understory, perhaps. Does the yellow signal caution and cowardice, or does it hearken warmth and renewal?

Divine G’s hoodie doesn’t stay on for the extent of the film. It’s absence goes unremarked as well, but we watch as grief and the cruelty of incarceration wears through RTA’s chosen leader and removes him from his station. Colman Domingo plays the theater-obsessive beautifully, though not a stretch given his own profession. It’s the scenes later in the film, during Divine G’s crisis and ultimate redemption, where his performance takes on a remarkable depth. He has to play mean and self-destructive, but as a man at the mercy of a boundlessly cruel system. The purple hoodie may have been his suit of armor, but it couldn’t save him.

Sing Sing is a notable story in the currently escalating awards race. Much has been said about A24’s decision to release the movie in the summer as opposed to the more prestige-favoring winter season. The studio/distributor has been accused of mishandling the release of the film and putting more of its resources instead behind Brady Corbet’s The Brutalist, rendering Sing Sing under-discussed and under-awarded. It is a surprise given some of the film’s bona fides: a dramatization of a very real and inspirational story featuring performances by alumni of Rehabilitation Through the Arts portraying themselves, in addition to a very committed and passionate performance by Domingo, who is widely beloved. Sing Sing toes a fine line between sentiment and realism, thanks in part to its aesthetic. Greg Kwedar’s direction and the film grain and handheld vérité style of cinematographer Pat Scola reminded me of another recent work about artistic commitment in the face of unthinkable adversity: 2019’s Sound of Metal, which featured a similarly epicentric peformance by Riz Ahmed (who lost the Best Actor statue to Joaquin Phoenix’s Joker).

In Sing Sing, the eponymous prison is shot not as a hellhole but as a spare fortress of tortured beauty. The daylight as its seen from the yard or a desolate stairwell feels like it’s escaping through the edges of the frame. And the workshop scenes in the prison’s auditorium are magical, the actors filling up the room with their performances, their acts of freedom, as the slightly shaking camera indulges the viewer to believe here I am in the room with them.

After leaving the theater over the summer, I had the feeling shared by many: more people should see Sing Sing. It’s a deeply tender project about a very difficult topic. My immediate admiration for the film did come with a hesitation, however. For a film set in prison, and versed in the day-to-day reality of incarceration, its critique of the carceral system is lacking in teeth. I understand the film is not meant as an investigation into the corruption and wrongness of public and private prisons, nor does it pitch itself as an abolitionist work of art. It’s a portrait of hope and a celebration of a program which has brought dignity into a dehumanizing system. One could argue that it’s not the movie’s job to argue for prison abolition. No one would have financed such a project at this scale, nor would A24 distribute it. I’m still left feeling that Sing Sing stopped short of making too pointed a statement about the ongoing horror of mass incarceration or the prison industrial complex.

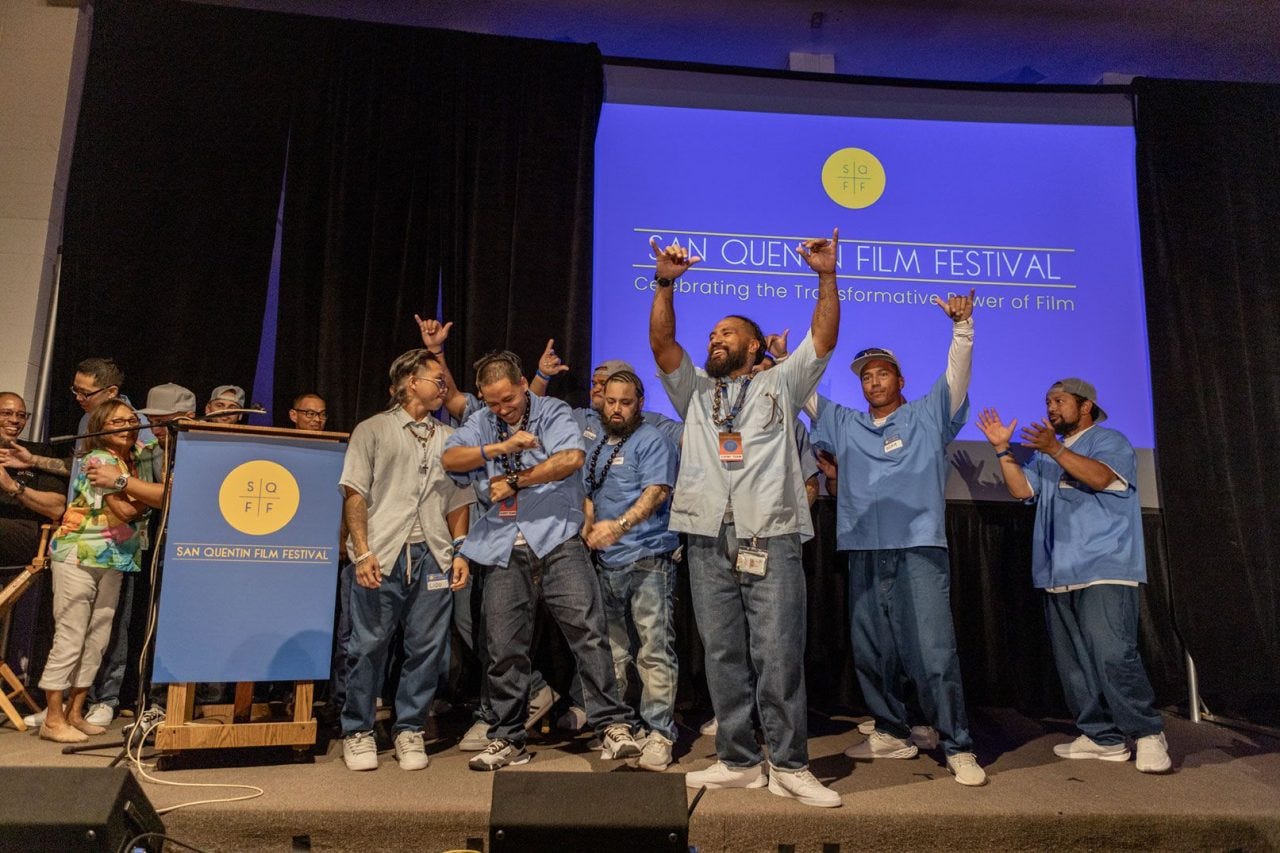

An advance screening of the film took place at the Sing Sing Correctional Facility last year, before its initial release in July. It was also screened at the inaugural San Quentin Film Festival - the first ever held in a prison - in October. And in January, as the film returned to 500 theaters to kick-off its awards push, it simultaneously became available to more than a million incarcerated people in the U.S. via a three-way collaboration among A24, RTA, and Edovo, a non-profit organization which has created a nationwide education and upskilling platform for people in jails and prisons. Edovo’s materials are accessed through state-issued tablet computers in prison and this is where the film is being made available. On the release, Edovo founder and CEO Brian Hill said, “with Sing Sing, we’re giving incarcerated individuals an opportunity to see themselves in a story of resilience and transformation, and to feel inspired to imagine new possibilities for their own lives."

Edovo is not currently available at the Sing Sing Correctional Facility in New York.

I am not aiming to be overly critical of the film, which I loved and think more people should see. Nor am I critiquing Rehabilitation Through the Arts, an essential program which operates in direct opposition to the prison-as-punishment paradigm, and has proven that an approach based on dignity can result in a 3% recidivism rate for its alumni (compared to a national average of 60%.) But we as viewers should not be content to have our liberal sensibilities flattered by a feel-good story of the arts making a difference. Not when our country continues to invest so heavily in policing and prisons. Not when it remains incredibly difficult for most people in American prisons and jails to access free physical books. A systemic turn towards tablets and e-reading has resulted in a selection of reading materials that is limited, censored, and costly. Many facilities charge $1 per e-book (on top of the cost of accessing a tablet), while the average hourly wage for incarcerated people the U.S. is $0.63.

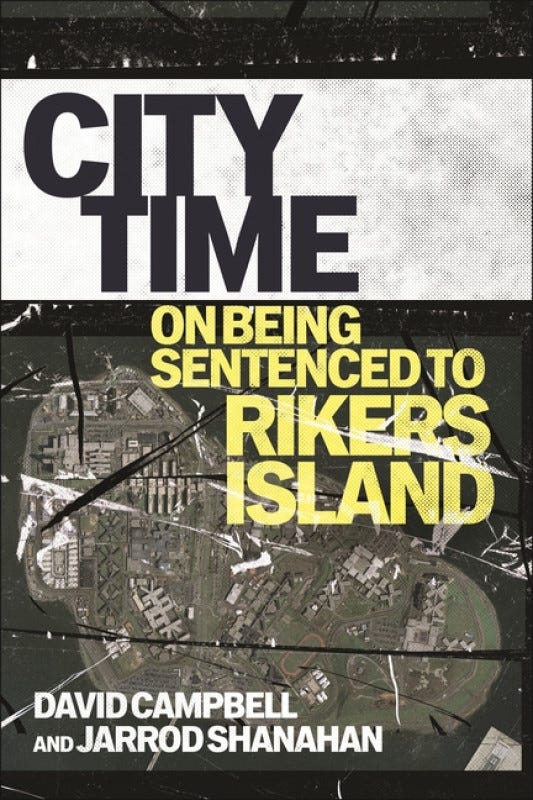

Prison has been on my mind lately for a couple of reasons. Firstly, as we have all likely heard about, more than 1,000 incarcerated people fought the Los Angeles wildfires earlier this month while earning between $5-$10 per day. Even those people working 24-hour shifts to respond to the fires earned a maximum of $26.90, according to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. The second reason is a recent talk I attended at the Center for Brooklyn History. The subject was a new book, City Time: On Being Sentenced to Rikers Island and it featured the co-authors, David Campbell and Jarrod Shanahan, in conversation with Donald Washington, Jr. All three men on stage had spent time behind bars at Rikers, the correctional facility operated by the City of New York which is planned to close in 2027 as the city moves to a “borough-based” jails system. They discussed the abject conditions at the facility, with Campbell remarking that “jail is designed to make you dumb” by making materials for reading, writing, or any intellectual study scarce and difficult to procure. He was jailed during the initial outbreak of Covid-19 in March 2020, when the NYC Department of Correction took no action to mitigate the spread of the disease inside the complex and advised those incarcerated to drink green tea to ward off sickness.

During the Q&A portion of the event, a woman asked a question in a sort of faltering way that amounted to “well…what can we do?” Shanahan, an abolitionist and professor of criminal justice, took the mic and calmly replied, “the bridge to Rikers Island is a choke point. Get enough people and you can form a barricade. Only buses off the island, no buses onto the island. Demand that they close Rikers now.”

The crowd sat in stunned silence. Then slowly, tentatively, we began to applaud.