What If Music Went On Strike?

Examining the power of music workers during an historic labor movement in America

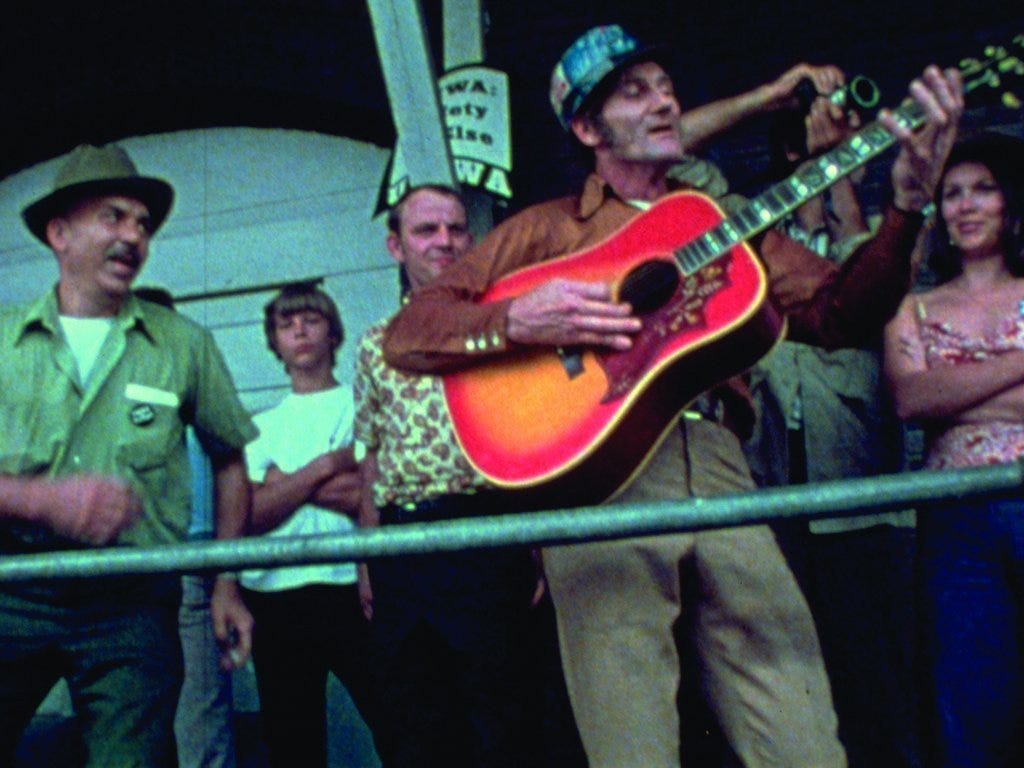

The 1976 documentary Harlan County, USA, directed by Barbara Koppel, opens with a ballad sung by a gaunt old man from a porch rocking chair. The song is “42 Years” and it refers to the time spent by the man, Nimrod Workman, working underground in the coal mines of Kentucky. His voice overlays footage of an early morning in Brookside, Kentucky, a “company town” created and underwritten by the Eastover Mining Corporation. Workman’s song recounts the brutal toll mining took on his body, particularly how the toxic air of the mine affected his lungs. After he concludes the song, he remembers a story of the mine foreman telling him to make sure he protected the company pack mule, to keep it away from any area a rock might fall and maim it.

I said, “Well what about me? If a rock had fallen on me?”

He said, “We can always hire another man, but you gotta buy that mule.”

Workman’s ballad, so sparse and brittle, is part of a deep tradition in Appalachia: the use of song to discuss hardship in labor, particularly in the industries of coal and textiles, which accelerated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Songs from this Appalachian tradition were a weapon against exploitation, not only to bolster morale within communities under foot of seemingly omnipotent companies, but also to speak righteous truth to said power. The roots of this oral tradition extend to the use of song amongst enslaved African people in the Americas: field hollers and spirituals carried power in dual directions: a way to covertly undermine the oppressors and bring solace to the oppressed.

I first encountered the Applachian heritage of labor songs in 2015, when I spent my spring break in West Virginia. The trip was meant to provide a group of students an “immersive understanding” of fossil fuels through an environmental justice lens. It was coordinated by Tom Breiding, a musician originally from Wheeling, West Virginia. Tom’s songs focus on the continued struggle amongst working people in his home state, and he holds a deep affiliation with the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), the union which the miners of Harlan Country were fighting to join. The week in West Virginia left a deep impression on me, and the lessons of that time are still unfolding in my life. The labor movement in America has a renewed energy, and we seem to be at a moment of historic potential in the fight for more fair and equitable work. So naturally I raise the question: where does music, both the art and the industry, fit into all of this?

Music has not been as intrinsically tied to the labor movement of the 2020s as it was for the Kentucky coal miners or textile millers in the Carolinas and I’d argue one reason is that the music industry has become an arena for a labor struggle itself. With this year’s Writers Guild of America (WGA) and Screen Actors Guild (SAG-AFTRA) strikes, the latter of which is ongoing, questions around the striking power of another major arts profession - music - began to enter the discourse.

The Los Angeles Times dove into the questions of musicians’ labor power in July, with author August Brown identifying the main issue undermining the ability of many music workers to organize effectively: they’re not employees, but rather legally considered independent contractors.

Consider your top artist from last year’s Spotify Wrapped. Chances are this person releases their music through a record label, who handles the work of publishing, promoting, and monetizing. That artist is not an employee of the label, but rather an independent contractor licensing their work, sharing a portion of the profit with the label for its effort. And according to the National Labor Regulations Board (NLRB), only those who are legally considered “employees” can form a recognized union in their workplace. And there is a musician’s union: the American Federation of Musicians (AFM), which is better known for representing musicians who are members of an orchestra, or are employed by a film studio to compose a score, but according to the AFM website, so-called “freelancers” are not disqualified from membership. However, their ability to organize and demand better payment from a venue or promoter, for example, is limited. The venue or promoter is not employing the artist, they’re just paying a freelancer for their services. The collective-bargaining ability for so many musicians, producers, and songwriters is kneecapped simply by this issue of classification.

The AFM also used to wield a great deal more power within the music industry, and in 1942 there was in fact a strike - AFM members were concerned that radio stations and record labels would collude to utilize the new technology of LPs to undercut musicians’ earnings from live performance. The result was contracts between AFM membership and record labels, which required the latter to pay a portion of record sales into a public trust: The Music Performance Trust Fund. For a brief and remarkable time in America, this Trust was the biggest buyer of music and employer of musicians in the country.

Then, as the story goes, the wave of anti-union sentiment that overtook the U.S. government in the 1950s undid a great deal of the AFM’s victories. Legislation such as the Taft-Hartley Act, from 1947, severely limited the actions that unions can take, and even pre-dating that is Anti-Trust Law which prohibits much of the collective action that music workers can take, such as withdrawing their songs from digital publishing platforms as a method of protest. Federal law would deem such an action as monopolistic behavior, and songwriters could be sued on that basis. Similarly, if artists attempted to collectively bargain their way toward better royalties from music streaming services, it could be seen as “price fixing” or otherwise an anti-free market activity.

One could be forgiven for seeing the current state of labor within the music industry as dire. The WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes, as many have pointed out, is responding not only to the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, but to an overall industrial progression that the pandemic accelerated. There is still a great deal of money in TV, film, and music, but instead of being distributed fairly it has only been consolidated more and more tightly. This has enriched a small number of people at the top who wield disproportionate power over their industries, meanwhile the compensation for working artists has remained stagnant as the profits hang suspended above them, intentionally guarded and out of reach.

In the last two years, as the music industry has tried to shake off the long tail of the pandemic, long-simmering frustrations around the economics of touring have boiled over. The prevailing notion since the popularization of music streaming and the decline in physical media sales has been that touring is where musicians really make their money. There was quite a bit of truth to this idea until the rush back to live concerts in 2021 created a bottleneck and drove up the operating costs for touring musicians exponentially. Conversely, the performance fees that most touring musicians receive are still on par with what they would have seen in 2018.

The result: cancelled tours from the likes of Santigold and Animal Collective, both of whom called out economically unsustainable factors in their decision. Cancellations abound in live music nowadays: for cost, for Covid, for the mental health of the artists. The whole enterprise seems to have been squeezed to its absolute limit, with the precariousness even seeping into the environment of the concert hall. We’ve probably all seen at least one video of something thrown at a performer onstage in the past year, and I’d wager I’m not alone in the opinion that the live music experience just feels noticeably worse.

And as if it couldn’t get more bleak, the past two months have seen a great deal of discourse around “merch cuts”. For those who may be unfamiliar, part of the reason touring has been a viable source of income for many performing musicians is that they sell merchandise on the road, and buying a t-shirt, tote bag, or vinyl record at an artist’s concert is seen as a great way of supporting them directly (the unsaid part of this equation is an assumption that the artist won’t be making any real money from ticket sales.)

In September, the artist Sara Beth Tomberlin, who performs as Tomberlin, publicized the artist merch policy of Wolf Trap, a DC-area performing arts venue, where she was performing as an opener for Ray LaMontagne. The venue would retain 30% of gross sales on “soft merch,” or anything that’s not recorded music (shirts, etc.), 10% for vinyl and CDs, and then an additional 5% of total gross sales for the use of the venue’s credit card readers and 6% of gross for sales tax. Effectively, Wolf Trap would take a 41% cut for all “soft merch” Tomberlin would sell that night, which the artist claimed would leave her with $0 profit. She opted to not sell merch at the venue, the only other option being to raise the cost of items sold by a proportionate percentage.

Tomberlin’s protest was the latest in a recent string of artists speaking out on the specific topic of merchandise cuts from venues, which is a symptom of the monopoly that companies such as AEG and Live Nation hold over live music. The problem, like the companies perpetrating it, is international. The UK band Dry Cleaning, in order to avoid garnishing a significant portion of the merch sales to the O2 Kentish Town Forum, opened a popup shop in a pub near the venue and sold at 100% profit the afternoon before their show.

Merch cuts have garnered a great deal of chatter online, and in a seemingly wild about-face Live Nation announced that it would be eliminating merchandise garnishments at many of its venues, and paying both opening and headlining acts up to $1,500 as a travel expense stipend. The program turned out to be a partnership with country music legend Willie Nelson, and despite the surprise of such generosity from an industry behemoth, many were quick to speculate ill intent on the part of Live Nation. By making their venues more attractive for artists and booking agents, the company would only deepen its monopoly on the live entertainment industry, pushing independent venues further toward the edge of bankruptcy and closure. And, notably the “On the Road Again” program, named for Nelson’s famous tune, would only last through the end of 2023.

There is an existential element to the question of labor practice within the music industry, namely a fear that if intervention does not come soon, there may be irreversible changes to who can afford to play live music, and who can afford to attend. To finally acknowledge the elephant-sized friendship bracelet in the room, in a year marked by so much turmoil in the live music industry it’s worth noting that Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour is set to become the most profitable concert tour of all time, and still only barely overtook Beyonce’s Renaissance tour for the most profitable thus far in 2023. As a piece in Business Insider raised, the gargantuan Eras tour seems to spell an existential threat for the small and mid-size venue market.

One wouldn’t necessarily think of these things in competition: Taylor Swift isn’t going to play Bowery Ballroom, so why would Eras matter in that regard? The answer is in the buying power of the consumer. As it was well-publicized at the time, Ticketmaster’s new “dynamic pricing” model for some of the highest-profile concerts creates exorbitant face value. The cost of tickets to see Taylor quickly became fodder for morning show hosts and sportscasters alike, but the question lying just around the corner is what happens if the live music experience, writ large, continues on a trend towards consolidation? If the biggest artists in the world are able to command a premium for their in-concert experience, with the power brokers of the industry behind them, will the majority of ticket-buying consumers be forced to choose: one big show or a handful of smaller ones for the year? And if there is no more market for small or mid-size venues, nor the artists who would play them, then what chance to they have to survive?

As I’ve said, the outlook is bleak, but there is a great deal being done to try to establish better labor practice in the music industry. The Union of Musicians and Allied Workers (UMAW), formed in 2020 to take direct action to support those affected by the pandemic and has quickly become one of the foremost advocates for a more equitable economic model for music workers, a broad category including songwriters, musicians, producers, DJs and others. One of UMAW’s first campaigns was for Justice at Spotify, which presented a list of demands to the streaming company including a better royalty pay rate, more transparency in their contracting process, and a cessation of legal action against artists. They have organized for better pay rates for performers at the annual South By Southwest festival and last year launched a campaign entitled #MyMerch, which calls on venues to do away with the garnishments that Tomberlin and others have more recently spoken against. They have created a database of venues which have taken the pledge not to take a cut from artists.

UMAW offers a great deal of hope for a better future in music primarily because its leadership seems to have a better understanding of the contemporary industry landscape than does the American Federation of Musicians, which has drawn some criticism for an elitist separation of “professional” musicians and “freelancers.” The question many seem ready to raise is can UMAW effectively organize music workers into the type of bargaining position that won the Writer’s Guild of America its most recent contract?

Unfortunately that question seems to miss the point somewhat. In researching this piece I spoke to a few friends who are involved in labor organizing themselves, though in industries outside of music. Having gained their perspective, I believe the future for music workers may be best determined from looking outside of a guild unionism framework and toward current examples that mirror their own place within the industry.

One of these friends offered two examples that might unlock a potential path forward for music. There have been recent organizing victories for Amazon workers, both drivers and those who work in fulfillment centers. Amazon subcontracts much of its fulfillment work to Delivery Center Partners, or DSPs, who are the legal employers of delivery workers even though Amazon’s branding pervades. This organization is leveraging legislation like Taft-Hartley to insulate and protect Amazon as the parent company. Major music labels like Sony and Columbia will adopt this same strategy by utilizing smaller “family” labels for contracting. However, earlier this year the Teamsters were able to successfully hold a union election at a DSP in Palmdale, California. The workers voted to form a union but before it could receive recognition from the National Labor Regulations Board, Amazon terminated its contract with the DSP thereby clearing itself of the responsibility to negotiate with the union for better pay and working conditions.

The other example this friend offered is Los Deliveristas Unidos, a collective of app-based delivery workers who were initially organized by Workers Justice Project, and through many direct actions and advocacy were able to influence the New York State Government to pass legislation which offers greater protections, better pay, and working conditions.

The reality is that many music workers who are relying on artistic output for their livelihood have been classified as gig workers, and this has robbed them of so much bargaining power, but the example of Los Deliveristas proves that workers don’t actually need a union, especially a guild union, to effectively organize. And in the case of music workers, the path toward a more equitable economic model begins with lobbying the government to change the legislative playing field.

For example, UMAW has attached its support to a bill written by Rep. Rashida Tlaib which would create a streaming-specific royalty, requiring companies like Spotify, Amazon, and Apple to pay a performance-based sum directly to musicians who publish on their service, over and above the existing payment scheme which often has to pass through a publisher and/or music label before any money makes it to the artist.

Several bills have attempted to create a carve-out in antitrust law that would allow independent contractors to collectively bargain with the companies they are providing services to. If such a bill were to pass, it would be a win for music workers and would lay the groundwork for further organizing outside of a more traditional union framework. The dream of a SAG or WGA-style guild for music may not be in the cards, and so the priority should be to organize in a way that directly addresses the economic reality that music workers are facing.

That’s not to say that support from existing unions wouldn’t go a long way. As it stands there doesn’t seem to much publicized partnership or solidarity between UMAW and its forebear, the AFM. A stronger partnership, even a symbolic one, could move the needle on the level of attention and advocacy needed to win legislative battles. Likewise, solidarity and support from WGA, SAG-AFTRA and even IATSE (the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees) could help to build more of a coalition of artistic professionals working toward a shared goal of a more equitable stake in the economy that their art helps create.

There has perhaps never been more desire for change within the music industry, and this is another reason for hope. The energy is there, and people are fed up, and these are both powerful levers to make real and sustainable change. But it will take a great deal of courage as well, courage that has always been required and has always been found in the laborers of America.

If you need support in your workplace, please contact the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee (EWOC)

This month’s playlist is short, since the article is so dang long. Here are some labor songs I listened to as I wrote it: